June 12, 1998 - by Mauro Pedrotti, Coro della SAT Director

Natural harmonies

A revolution - thus can be defined, without risk of exaggeration, the advent of Michelangeli among the ranks of harmonizers of the Coro della SAT. It was during the fifties, Luigi Pigarelli and Antonio Pedrotti had a firm grip on the artistic direction of the Choir, which followed willingly, save a few bold digressions (such as the elaboration in a minor key of Montagnes valdotaines by Teo Usuelli or Aladar Janes' genial invention, Soreghina) along the path mapped out for it by the two "bosses". A path which was, in fact, a natural continuation of the one embarked upon by the first singers in 1926 when they formed the choir. Pigarelli and Pedrotti - in particular the former - had started out precisely with those arrangements improvised "by ear" for the occasion, which were as full of innate musicality as they were of naïve enthusiasm.

The harmonizations of Michelangeli - and here lies the secret of their "revolutionary" impact - could certainly not have come about spontaneously, what with all their sophisticated harmonic effects woven into a polyphonic structure far removed from the model to which the singers were used. But Michelangeli too, after the bosses, had intuited the performance capacities of the choir, though he adapted them to his own sensibility and artistic requirements. A revolution it was, but one embraced in a natural way, as if the great pianist and the choir had had to meet and had always known the fact. All it took was a chance event, a second impulse to the first spark that had ignited at Brescia in 1936, at the first premonitory meeting. And so, as in some magic design where all the details materialize one after another, came the second flash - in 1949 Michelangeli was called to the Conservatory of Bolzano to run a course of master classes. In the same town lived and worked Enrico Pedrotti, one of the founding brothers of the SAT Choir. Another part of the magic design materialized. The first spark of Brescia bore its fruit in a human and artistic rapport which, from that moment, never ceased.

This subsequent encounter between the Maestro and Enrico Pedrotti - which marked the beginning of a close collaboration, of a reciprocal esteem and sincere friendship - produced the first harmonizations, on a series of beautiful songs of Piedmont, Lombardy and Provence: La pastora e il lupo, La bela al mulino, La scelta felice, Lucia Maria, Il maritino, La mia bela la mi aspeta.

Once the scores had been written, it was up to the choir to translate them into sound. The first, arduous trial was with La pastora e il lupo. It was 1954. I was not directly involved in the choir then - it was before my time - but I experienced the magic of those days through the tales told by those who were there: my father, my uncles and a few other "historic" figures. It was as if I was there, in the photography studio of the Pedrotti brothers (which was now also the seat of the choir after, for years, rehearsals had been held in my home, in Via Grazioli in Trento), and could hear the contrast between exclamations of marvel from those who were sufficiently musically trained to be able to perceive immediately the beauty of those harmonies, and moans and groans from those less open to novelty. These latter, to be honest, deserve some justification. This new music was a far cry, in fact, from the placid homophony and easy chords of Pigarelli's Pastora which had been the choristers' fare from the choir's foundation up until just after the war. The plot and characters were the same: the shepherdess, the lamb, the wolf, the knight, the rescue of the victim, the defeat of the wolf, the kiss as a "price" to pay (even if the Trentino version clearly diverges here and ends with the death of the lamb and the disconsolate cry of the pretty shepherdess). But the differences at a musical level were enormous. Melody, structure, rhythm, and harmony - all was different. That dream-like atmosphere so tangible in the Piedmontese song was an open door through which Michelangeli passed with all the energy of one who had something to say and had finally found the way to express himself, to unleash his artistic emotions in a medium other than the pianoforte, other than his beloved Chopin, Debussy, and Ravel.

Why?

It is not easy to answer this question. Gian Paolo Minardi in his essay on the rapport between Michelangeli and the SAT Choir (published recently in the book "Coro Sat - 70 years") observes that he often happened to notice the amazement of people in seeing the great pianist's name associated with the harmonization of alpine songs. And he suggests some possible ways of understanding this association: perhaps, the Maestro's love for those places (the same places where those songs originated) where he could enjoy the relationship with nature and its sounds; or, perhaps, the similar way in which both pianist and choir relate (the ultimate end in performance) to music.

Whatever the explanation, the result was extraordinary: the suspended chords, chromatic scales, the pedal point of the basses, the harmonies set in glorious polyphonic structure, the rhythmic changes, the timbres sought by Michelangeli opened up a new world for the choir, while the choir for its part offered itself to the Artist as an instrument pliant and at the same time creative, alive and full of vitality - overcoming without difficulty the initial perplexities regarding the enormous contrast between not merely the two Pastora s but two opposed modes of conceiving popular song.

Let us return to that rehearsal room, where on Friday evenings throughout the year, photographic equipment, lights and tripods were moved to make room for about twenty young and not so young choristers united by their common interest in and passion for music. Someone who knew how to write music would have diligently transcribed the individual parts from the original score, and these were then distributed. With a small harmonium to guide the voices, each section got done to the business of learning its own part, feigning indifference at the strange intervals. Silvio Pedrotti, the choir director, would get flustered, make the choir repeat the still unsure passages, correct the rhythm, suggest attacks - he too was surprised, amazed, trembling before something whose greatness he intuited long before the others, happy to be a witness at its birth. Little by little, the song took shape. Miraculously, moans and groans, perplexity and feigned indifference disappeared. And in their place appeared the music, the beauty, the harmony, and the magic of a popular treasure transformed into a masterpiece.

Sometimes, the Maestro was present at the rehearsals. Here is the memoir of Lino Zanotelli, one of those who took part in this extraordinary experience: "Standing, with his hand under his chin, eyes closed, a faint, sweet smile on his lips, he would express great joy and satisfaction in assisting at the birth of his songs. He would listen in silence to the parts sounding together. At the end, with a wisp of voice (as was his custom) almost timorous, barely able to be heard, with a nod of the head he would say: "Good."

But La pastora isn't the only one. With La bella al mulino one enters a totally new atmosphere, the indistinct outlines of which are suggested by the continual fluttering of the keyboard rather than by the solid, confined pentagram of the choir. In Lucia Maria, on the other hand, the pizzicato of the basses lightly sustains the melody, at the same time accentuating its dramatic quality which culminates, in the final section, in tragedy, underlined once again by the basses with a final chord which is also a cry of anguish. Or, yet again, La mia bela la mi aspeta: three verses each harmonized in a different way, almost paralleling the meaning of the text, while the final refrain closes with incredible tenderness on the words: "Valcamonica del mio cor" evoking nostalgia for those wild, silent landscapes so dear to the Maestro.

The jocular spirit of the Trentino song Le maitinade del Nane Periot is in contrast to the drama of war, the Provençal tragedy. Here rhythm and coloratura are everything, as the text unfolds with Nane singing the praises of his "morosa". The melody passes with naturalness from the baritones to the seconds, while the other voices have the task of harmonically livening the tale. At the end, then, an unexpected change of tonality (who ever was so daring in those days?) accentuates the brilliant and virtuoso character of the piece.

The choir greeted these first harmonizations with sincere enthusiasm after the initial perplexities and difficulties. So much so that the idea of putting on record also these latest important innovations (after the first experiences, in the '30s and '40s, with the standard repertoire) began to gain ground. And in fact, between 1956 and 1960 some LPs were released with the Odeon label, containing all the songs of Michelangeli's "first period" (including, besides those quoted, La blonde, La brandolina, and Era nato poveretto). These recordings mark and celebrate the artistic transformation of the SAT Choir - they made the choir famous for its interpretative skill and as an exponent of popular song not treated in rough, "poor" fashion but supported by a harmonic system of great musical value (and they also gave rise to the first criticisms of the "purists", who however were silenced once and for all by Massimo Mila).

In 1959 Michelangeli's rapport with the Conservatory of Bolzano came to an end - the Maestro left the city and his encounters with the SAT Choir dwindled. New songs however continued to appear: Entorno al fòch and Le soir à la montagne were added to the collection of the first harmonized songs and the Choir, which now was recording for RCA, recorded with the latter all its available heritage of Michelangeli's harmonizations, on diverse LPs between 1960 and 1969.

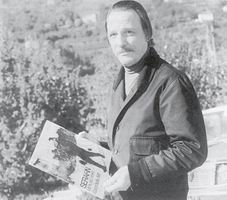

Next followed a series of Trentino songs that Silvio Pedrotti proposed to the Maestro during his summer visits to Rabbi in the alpine hut where he used to spend brief periods of rest and concentration. The repertoire was enriched with Serafin (an extremely sophisticated elaboration of a song in itself unusual in terms of Trentino folklore for its 5/4 rhythm) followed by La figlia di Ulalia and Che fai bela pastora: all recorded in 1972 on the seventh LP with RCA: a photo very dear to the Maestro - and naturally to the Choir - portrays him holding the record, which took the name of Serafin from the most representative song of the programme.

An interval of five years lapsed. Then in 1977 two more songs appeared, this time from Lombardy: lo vorrei and I lamenti di una fanciulla, which were included in the ninth LP. Three years later, the tenth disc appeared containing the now classic "innovation" by Michelangeli: Vien moretina, of Trentino origin, which bears the unmistakable signature of a final pianissimo arpeggio, suspended like a solitary petal in the "fine air" evoked by the text.

Meanwhile the choir had further polished its own performance and interpretative capacities. There had been some membership changes and a notable expansion of repertoire, with recordings of innovative contributions from musicians such as Renato Dionisi, Bruno Bettinelli, Andrea Mascagni, Giorgio Federico Ghedini, alongside the glorious Pigarelli and Pedrotti, who still remained unbeaten in terms of their prolific number of harmonized songs.

A period of silence followed, in which it seemed that Michelangeli's creativity had stopped, almost as if the beauty of the first Piedmontese songs, which had so attracted the Maestro, could no more be revoked. However, with another Trentino song in 1983 the miracle occurred again. A sweet lullaby, simple and linear, originating from the recollections of Rosa Pedrotti Daprà, my paternal grand-mother, succeeded in reawakening in him the desire to return to the instrument that, after the piano, he most loved: the human voice - more precisely, the voice of the SAT Choir. And the choir, believing that by now it had experimented all the harmonic inventions possible, was instead astonished by this latest creation. What one chiefly hears is the sweet melody entrusted to a soloist, but accompanied by a faint, submerged dazzle of off-beat arpeggios and glissandos in the tenors, while the baritones and basses, on the beat, have extremely measured semitone undulations. All Michelangeli's pianistic art, all his love for extreme sonorities, and his musical expressiveness were poured into these few lines, which also represent the extreme synthesis of his work as an elaborator of popular songs, and his spiritual testament in that they are the last lines he wrote.

How did the choir respond to 'Ndormènzete popin? First of all, with great respect, almost intimidated by such poetry and beauty hidden behind the technical difficulties of the piece. Then, little by little as they discovered its essence, the timidity gave way to joy and also a sentiment of pride - almost a spontaneous claim that, yes, it had to be just so, that he wrote the piece for us, all his admiration for us is in it, and we must respond in the only way that, we know, will be appreciated: with a performance of such quality as to translate into pure sound this so complex, yet precise, harmonic idea.

Berlin, May 1983. The programme of a new disc - eighteen songs - occupied us for almost four days in the recording studio. When it came to the turn of 'Ndormènzete popin, the faces of the recording director and technicians turned pale after the first audition, for fear that the technical and interpretative difficulties of the piece were such as to "stretch" out of all proportion the studio time allotted. But they were mistaken - after only two practice runs 'Ndormènzete popin came to birth, as is said of true masterpieces.

The Maestro, to whom we gave the first copy of the disc, appreciated the Choir's efforts and recognized its merit. He however had a reservation about the soloists, who in his opinion did not render with sufficient sweetness the subtle simplicity of the text. Since then, the idea of repeating that extremely difficult recording, on the strength of his observations, has been constantly present, and we finally programmed the song into the CD designed to celebrate the 70th anniversary of the choir's foundation in 1996. We were too late, unfortunately, to be able to gain his definitive approval. But the second version of 'Ndormènzete popin is our expression of gratitude and love to a great Musician and Friend and our homage to the extraordinary contribution he made to popular song and music in general.

NOTE: The full version of the second version of 'Ndormenzete Popin can be downloaded in mp3 format by clicking here.